Posted on May 15, 2008

|

| press.princeton.edu |

It is not news that the United States is in great trouble. The pre-emptive war it launched against Iraq more than five years ago was and is a mistake of monumental proportions—one that most Americans still fail to acknowledge. Instead they are arguing about whether we should push on to “victory” when even our own generals tell us that a military victory is today inconceivable. Our economy has been hollowed out by excessive military spending over many decades while our competitors have devoted themselves to investments in lucrative new industries that serve civilian needs. Our political system of checks and balances has been virtually destroyed by rampant cronyism and corruption in Washington, D.C., and by a two-term president who goes around crowing “I am the decider,” a concept fundamentally hostile to our constitutional system. We have allowed our elections, the one nonnegotiable institution in a democracy, to be debased and hijacked—as was the 2000 presidential election in Florida—with scarcely any protest from the public or the self-proclaimed press guardians of the “Fourth Estate.” We now engage in torture of defenseless prisoners although it defames and demoralizes our armed forces and intelligence agencies.

The problem is that there are too many things going wrong at the same time for anyone to have a broad understanding of the disaster that has overcome us and what, if anything, can be done to return our country to constitutional government and at least a degree of democracy. By now, there are hundreds of books on particular aspects of our situation—the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the bloated and unsupervised “defense” budgets, the imperial presidency and its contempt for our civil liberties, the widespread privatization of traditional governmental functions, and a political system in which no leader dares even to utter the words imperialism and militarism in public.

There are, however, a few attempts at more complex analyses of how we arrived at this sorry state. They include Naomi Klein, “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism,” on how “private” economic power now is almost coequal with legitimate political power; John W. Dean, “Broken Government: How Republican Rule Destroyed the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial Branches,” on the perversion of our main defenses against dictatorship and tyranny; Arianna Huffington, “Right Is Wrong: How the Lunatic Fringe Hijacked America, Shredded the Constitution, and Made Us All Less Safe,” on the manipulation of fear in our political life and the primary role played by the media; and Naomi Wolf, “The End of America: Letter of Warning to a Young Patriot,” on “Ten Steps to Fascism” and where we currently stand on this staircase. My own book, “Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic,” on militarism as an inescapable accompaniment of imperialism, also belongs to this genre.

We now have a new, comprehensive diagnosis of our failings as a democratic polity by one of our most seasoned and respected political philosophers. For well over two generations, Sheldon Wolin taught the history of political philosophy from Plato to the present to Berkeley and Princeton graduate students (including me; I took his seminars at Berkeley in the late 1950s, thus influencing my approach to political science ever since). He is the author of the prize-winning classic “Politics and Vision” (1960; expanded edition, 2006) and “Tocqueville Between Two Worlds” (2001), among many other works.

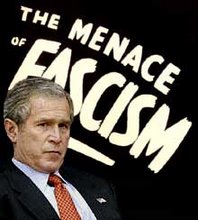

His new book, “Democracy Incorporated: Managed Democracy and the Specter of Inverted Totalitarianism,” is a devastating critique of the contemporary government of the United States—including what has happened to it in recent years and what must be done if it is not to disappear into history along with its classic totalitarian predecessors: Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and Bolshevik Russia. The hour is very late and the possibility that the American people might pay attention to what is wrong and take the difficult steps to avoid a national Götterdämmerung are remote, but Wolin’s is the best analysis of why the presidential election of 2008 probably will not do anything to mitigate our fate. This book demonstrates why political science, properly practiced, is the master social science.

Wolin’s work is fully accessible. Understanding his argument does not depend on possessing any specialized knowledge, but it would still be wise to read him in short bursts and think about what he is saying before moving on. His analysis of the contemporary American crisis relies on a historical perspective going back to the original constitutional agreement of 1789 and includes particular attention to the advanced levels of social democracy attained during the New Deal and the contemporary mythology that the U.S., beginning during World War II, wields unprecedented world power.

Given this historical backdrop, Wolin introduces three new concepts to help analyze what we have lost as a nation. His master idea is “inverted totalitarianism,” which is reinforced by two subordinate notions that accompany and promote it—“managed democracy” and “Superpower,” the latter always capitalized and used without a direct article. Until the reader gets used to this particular literary tic, the term Superpower can be confusing. The author uses it as if it were an independent agent, comparable to Superman or Spiderman, and one that is inherently incompatible with constitutional government and democracy.

Wolin writes, “Our thesis ... is this: it is possible for a form of totalitarianism, different from the classical one, to evolve from a putatively ‘strong democracy’ instead of a ‘failed’ one.” His understanding of democracy is classical but also populist, anti-elitist and only slightly represented in the Constitution of the United States. “Democracy,” he writes, “is about the conditions that make it possible for ordinary people to better their lives by becoming political beings and by making power responsive to their hopes and needs.” It depends on the existence of a demos—“a politically engaged and empowered citizenry, one that voted, deliberated, and occupied all branches of public office.” Wolin argues that to the extent the United States on occasion came close to genuine democracy, it was because its citizens struggled against and momentarily defeated the elitism that was written into the Constitution.

“No working man or ordinary farmer or shopkeeper,” Wolin points out, “helped to write the Constitution.” He argues, “The American political system was not born a democracy, but born with a bias against democracy. It was constructed by those who were either skeptical about democracy or hostile to it. Democratic advance proved to be slow, uphill, forever incomplete. The republic existed for three-quarters of a century before formal slavery was ended; another hundred years before black Americans were assured of their voting rights. Only in the twentieth century were women guaranteed the vote and trade unions the right to bargain collectively. In none of these instances has victory been complete: women still lack full equality, racism persists, and the destruction of the remnants of trade unions remains a goal of corporate strategies. Far from being innate, democracy in America has gone against the grain, against the very forms by which the political and economic power of the country has been and continues to be ordered.” Wolin can easily control his enthusiasm for James Madison, the primary author of the Constitution, and he sees the New Deal as perhaps the only period of American history in which rule by a true demos prevailed.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. I.U. has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is I.U endorsed or sponsored by the originator.)

The Nazis, Fascists and Communists were political parties before they became enemies of liberty and mass murderers.

No comments:

Post a Comment