Posted without comment, from:

LTC Bob Bateman, again.

No politics today, just some observations about a nation at war. Sort of.

Corridor Three

10:30 hours (local EST), Friday, 11 May 2007: Third Corridor, Second Floor, The Pentagon:

It is 110 yards from the "E" ring to the "A" ring of the Pentagon. This section of the Pentagon is newly renovated; the floors shine, the hallway is broad, and the lighting is bright. At this instant the entire length of the corridor is packed with officers, a few sergeants and some civilians, all crammed tightly three and four deep against the walls. There are thousands here. This hallway, more than any other, is the "Army" hallway. The G3 offices line one side, G2 the other, G8 is around the corner. All Army. Moderate conversations flow in a low buzz. Friends who may not have seen each other for a few weeks, or a few years, spot each other, cross the way and renew. Everyone shifts to ensure an open path remains down the center. The air conditioning system was not designed for this press of bodies in this area. The temperature is rising already. Nobody cares.

10:36 hours (local EST):

The clapping starts at the E-Ring. That is the outermost of the five rings of the Pentagon and it is closest to the entrance to the building. This clapping is low, sustained, hearty. It is an applause with a deep emotion behind it as it moves forward in a wave down the length of the hallway. A steady rolling wave of sound it is, moving at the pace of the soldier in the wheelchair who marks the forward edge with his presence. He is the first. He is missing the greater part of one leg, and some of his wounds are still suppurating.

By his age I expect that he is a private, or perhaps a private first class. Captains, majors, lieutenant colonels and colonels meet his gaze and nod as they applaud, soldier to soldier. Three years ago when I described one of these events on Altercation, those lining the hallways were somewhat different. The applause a little wilder, perhaps in private guilt for not having shared in the burden ... yet. Now almost everyone lining the hallway is, like the man in the wheelchair, also a combat veteran. This steadies the applause, but I think deepens the sentiment. We have all been there now. The soldier's chair is pushed by, I believe, a full colonel. Behind him, and stretching the length from E to A, come more of his peers, each private, corporal or sergeant assisted as need be by a field grade officer.

10:50 hours (local EST):

Twenty-four minutes of steady applause. My hands hurt, and I laugh to myself at how stupid that sounds in my own head. "My hands hurt." Christ. Shut up and clap.

For twenty-four minutes, soldier after soldier has come down this hallway -- 20, 25, 30. Fifty-three legs come with them, and perhaps only 52 hands or arms, but down this hall came 30 solid hearts. They pass down this corridor of officers and applause, and then meet for a private lunch, at which they are the guests of honor, hosted by the generals.

Some are wheeled along. Some insist upon getting out of their chairs, to march as best they can with their chin held up, down this hallway, through this most unique audience. Some are catching handshakes and smiling like a politician at a Fourth of July parade. More than a couple of them seem amazed and are smiling shyly. There are families with them as well: the 18-year-old war-bride pushing her 19-year-old husband's wheelchair and not quite understanding why her husband is so affected by this, the boy she grew up with, now a man, who had never shed a tear is crying; the older immigrant Latino parents who have, perhaps more than their wounded mid-20s son, an appreciation for the emotion given on their son's behalf. No man in that hallway, walking or clapping, is ashamed by the silent tears on more than a few cheeks. An Airborne Ranger wipes his eyes only to better see. A couple of the officers in this crowd have themselves been a part of this parade in the past. These are our men, broken in body they may be, but they are our brothers, and we welcome them home.

This parade has gone on, every single Friday, all year long, for more than four years.

Last week, I noted the disturbing reports about the ethics of Americans in Iraq and drew parallels to the increase in cheating in American schools. I was light on the commentary, and will remain so to some degree. But what has me stewing recently is Haditha.

I should note now that I am a long time admirer of individual Marines, I have been a member of the Marine Corps Association for more than a decade (though my membership has lapsed now), I write for Marine Corps Gazette upon occasion, and I believe that the Marines are necessary and useful. That being said, I am now worried for the future of the Corps.

The New York Times, by the way, deserves kudos for assigning reporter Paul von Zielbauer to this series. I have no idea who this guy is, and so far as I know, never read any of his work before this. But he is covering the trials of the officers in the Haditha killings, and doing so as well as anyone I have ever seen. His stories are accurate, non-sensationalistic, but hard-hitting on several levels at the same time.

One final note on Haditha as a phenomena, before I get cranked up: Haditha, or more accurately the trials of the Marine officers up the chain from the events in Haditha, is something that you will not see anywhere else. It will be forever a part of our national shame that things like Haditha (and Mahmudihyah, and Abu Ghraib, etc) occur in war. As Eric noted some time ago, it does not seem possible to wage a "perfect" war (as oxymoronic as that construction is) in which nothing like this ever happens. But the fact that we are having court martials matters. The fact that we are trying, in public, officers in the chain of command. The fact that reporters are allowed to cover the trial, and the reports are appearing in our largest papers. All of this matters, and does give me hope. In more ways than may be apparent. It matters.

Now, for the disturbing stuff: The first of these stories, which you can read here, is in my opinion a sign of internal moral rot among people like me: field grade infantry officers. Majors, lieutenant colonels, and full colonels are collectively called "field grade" officers. We are supposed to be more experienced, wiser, less likely to lose our heads and more likely to listen with openness. That is what age and experience, and perhaps some moderate wisdom, is supposed to give you. But what this story tells me about is a peer of mine, another LTC (albeit a Marine) was so blinded by his love of his unit that he blew off his two senior officers and the evidence that, yes, some of his men may have killed innocents, and refused to investigate. This does not speak well for the culture of the Marine Corps, or their future.

But it was actually the next story that really made me worry for the Corps, because this one involves the general in command. You see, by the time you make full Colonel, you are in theory the epitome of everything that service values. You are among the top 1 percent of that service. If you make general, this is even more the case. If this is true, then as I said, I fear for the Corps.

When you read the story, perhaps you may see why.

A few highlights:

The general who led a division in charge of the marines who killed 24 Iraqi civilians in Haditha in 2005 testified Thursday that he was kept from weighing accusations that the killings were illegal because his subordinate officers withheld information for nearly three months.

[Major] General [Richard A.] Huck said he had not learned until February 2006 about inquiries into the deaths by Time magazine because his own chief of staff and regimental commander kept him in the dark."

These lines indict the colonels below Major General Huck. I leave it to you to read these next selections and decide what they mean.

General Huck said he had made a list of all the officers and enlisted men who could have reported the Haditha killings as a possible law of war violation but did not. They ranged from senior officers to sergeants and radio operators who heard reports from the field that day.

...and later in the story:

For instance, he said he had learned within hours of the episode that women and children had been killed, and acknowledged that his own rules required investigation when a "significant" number of civilians died in actions involving marines. But later he said he saw no reason to look into how a "big" number of civilians had died in Haditha.

General Huck pointed out that his superiors -- including General Chiarelli and his predecessor, and Maj. Gen. Steve Johnson, the top Marine commander in Iraq at the time -- had received many of the field reports about the Haditha civilian deaths that he had received, and that none had opened an inquiry until the Time reporter, Tim McGirk, started asking questions.

Finally, at the end of the story is a short passage that really makes me worry for the Corps. If this trend continues, they may accidentally destroy themselves. To understand why I fear that conclusion you need a little history.

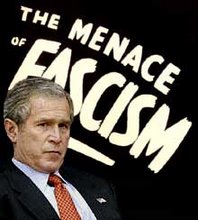

There was once a military force that got involved in politics. During a period of turmoil and perhaps a nationwide emotional malaise in their country, the officers of this military force became deeply enmeshed with a political party which had foisted a story that in the last war (which that nation had lost), the real reason for the loss was that the military had been "betrayed" with a "stab in the back" by soft-headed politicians and journalists on the home-front. The political party played up the idea that the military was still on captured ground at the end of that war, and that the defeat was not, therefore, a military one. This appealed to the ego of those military officers, and they promulgated the legend, and bound themselves to that party.

And no, I am not talking about Vietnam (but the parallel is scary). You can look up the history that I am referring to yourself. OK, so here is what pissed me off (Tim McGirk is a reporter for Time magazine):

The day's first witness, First Lt. Adam P. Mathes, the Company K executive officer at the time, said he and the battalion commander and the battalion executive officer had collectively dismissed Mr. McGirk's questions because they had considered them "sensational" and politically motivated.

"The questions were questionable," Lieutenant Mathes said, testifying by video link from Kuwait, where he is stationed. "It sounded like bad, negative spin. We tried to weed out the grievances that Mr. McGirk had against the Bush administration."

He said Mr. McGirk had seemed to have an antiwar agenda. "This guy is looking for blood," Lieutenant Mathis testified, "because blood leads headlines."

Here's a message for young 1LT Mathes: Lieutenant, it is not your goddamned job to screen for the political agenda of any damned civilian reporter. You are not to decide what a reporter can and cannot ask, beyond the completely reasonable limitations of Operational Security (OPSEC). You swear, like me, an oath to the Constitution. Not this party or that, not this officer or that ... to the United States Constitution. Remember that, Lieutenant. The same directive applies to your major. Pass it on. If I ever meet him, I will tell your battalion commander my own damned self.

OK, that is enough of that for a while.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. I.U. has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is I.U endorsed or sponsored by the originator.)

The Nazis, Fascists and Communists were political parties before they became enemies of liberty and mass murderers.

Friday, May 18, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment