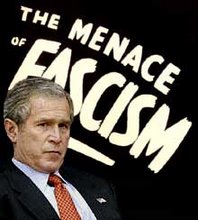

It's difficult to tell the difference. The Horror, the horror!

WASHINGTON: Senator John McCain arrived late at his Senate office on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, just after the first plane hit the World Trade Center.

"This is war," he murmured to his aides. The sound of scrambling fighter planes rattled the windows, sending a tremor of panic through the room.

Within hours, McCain, the Vietnam War hero and famed straight talker of the 2000 Republican primary, had taken on a new role: the leading advocate of taking the American retaliation against Al Qaeda far beyond Afghanistan. In a marathon of television and radio appearances, McCain recited a short list of other countries said to support terrorism, invariably including Iraq, Iran and Syria.

"There is a system out there or network, and that network is going to have to be attacked," McCain said the next morning on ABC News. "It isn't just Afghanistan," he added, on MSNBC. "I don't think if you got bin Laden tomorrow that the threat has disappeared," he said on CBS, pointing toward other countries in the Middle East.

Within a month he made clear his priority. "Very obviously Iraq is the first country," he declared on CNN. By Jan. 2, McCain was on the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt in the Arabian Sea, yelling to a crowd of sailors and airmen: "Next up, Baghdad!"

Now, as McCain prepares to accept the Republican presidential nomination, his response to the attacks of Sept. 11 opens a window onto how he might approach the gravest responsibilities of a potential commander in chief. Like many, he immediately recalibrated his assessment of the unseen risks to America's security. But he also began to suggest that he saw a new "opportunity" to deter other potential foes by punishing not only Al Qaeda but also Iraq.

"Just as Sept. 11 revolutionized our resolve to defeat our enemies, so has it brought into focus the opportunities we now have to secure and expand our freedom," McCain said at a NATO conference in Munich in early 2002, urging the Europeans to join what he portrayed as an all but certain assault on Saddam Hussein. "A better world is already emerging from the rubble."

To his admirers, McCain's tough response to Sept. 11 is at the heart of his appeal. They argue that he displayed the same decisiveness again last week in his swift calls to penalize Russia for its incursion into Georgia, in part by sending peacekeepers to police its border.

His critics charge that the emotion of Sept. 11 overwhelmed his former cool-eyed caution about deploying U.S. troops without a clear national interest and a well-defined exit, turning him into a tool of the Bush administration in its push for a war to transform the region.

"He has the personality of a fighter pilot: When somebody stings you, you want to strike out," said retired General John Johns, a former friend and supporter of McCain who turned against him over the Iraq war. "Just like the American people, his reaction was: Show me somebody to hit."

Whether through ideology or instinct, though, McCain began making his case for invading Iraq to the public more than six months before the White House began to do the same. He drew on principles he learned growing up in a military family and on conclusions he formed as a prisoner in North Vietnam. He also returned to a conviction about "the common identity" of dangerous autocracies as far-flung as Serbia and North Korea that he had developed consulting with hawkish foreign policy thinkers to help sharpen the themes of his 2000 presidential campaign.

While pushing to take on Saddam Hussein, McCain also made arguments and statements that he may no longer wish to recall. He lauded the war planners he would later criticize, including Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Vice President Dick Cheney. (McCain even volunteered that he would have given the same job to Cheney.) He urged support for the later-discredited Iraqi exile Ahmad Chalabi's opposition group, the Iraqi National Congress, and echoed some of its suspect accusations in the national media. And he advanced misleading assertions not only about Saddam's supposed weapons programs but also about his possible ties to international terrorists, Al Qaeda and the Sept. 11 attacks.

Five years after the invasion of Iraq, McCain's supporters note that he became an early critic of the administration's execution of the occupation, and they credit him with pushing the troop "surge" that helped bring stability. McCain, though, stands by his support for the war and expresses no regrets about his advocacy. In a written statement, he blamed "Iraq's opacity under Saddam" for any misleading remarks he made about the peril it posed.

The Sept. 11 attacks "demonstrated the grave threat posed by a hostile regime, possessing weapons of mass destruction, and with reported ties to terrorists," McCain said in the statement, by e-mail. Given Saddam's history of pursuing illegal weapons and his avowed hostility to the United States, "his regime posed a threat we had to take seriously." The attacks were still a reminder, McCain added, of the importance of international action "to prevent outlaw states - like Iran today - from developing weapons of mass destruction."

McCain has been debating questions about the use of military force far longer than most. He grew up in a family that had sent a son to every American war since 1776, and international relations were a staple of the McCain family dinner table. McCain grew up listening to his father, Admiral John McCain Jr., deliver lectures on "The Four Ocean Navy and the Soviet Threat," closing with a slide of an image he considered the ultimate factor in the balance of power: a soldier marching through a rice paddy with a rifle at his shoulder.

"To quote Sherman, war is all hell, and we need to fight it out and get it over with, and that is when the killing stops," recalled Joe McCain, McCain's younger brother.

Vietnam, for McCain, reinforced those lessons. He has often said he blamed the Johnson administration's pause in bombing for prolonging the war, and he credited President Richard Nixon's renewed attacks with securing his release from a North Vietnamese prison. He has made the principle that the exercise of military power sets the bargaining table for international relations a consistent theme of his career ever since, and in his 2002 memoir he wrote that one of his lifelong convictions was "the imperative that American power never retreat in response to an inferior adversary's provocation."

But McCain also took away from Vietnam a second, restraining lesson: the necessity for broad domestic support for any military action. For years he opposed a string of interventions - in Lebanon, Haiti, Somalia and, for a time, the Balkans - on the grounds that the public would deplore the loss of life without clear national interests.

In the late 1990s, however, while McCain was beginning to consider his 2000 presidential race, he started rebalancing his views of opposing needs to project American strength and to sustain public support. The 1995 massacre of 8,000 unarmed Bosnian Muslims at Srebrenica under NATO's watch struck at his conscience, he has said, and in addition to America's strategic national interests McCain began to speak more expansively about America's moral obligations as the only remaining superpower.

McCain's aides say he later described the American airstrikes in Bosnia in 1996 and in Kosovo in 1999 as a parable of political leadership: McCain, Senator Bob Dole and others had rallied support for the strikes despite scant support in the polls.

"Americans elect their leaders to make these kinds of judgments," McCain said in the e-mail message.

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. I.U. has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is I.U endorsed or sponsored by the originator.)

The Nazis, Fascists and Communists were political parties before they became enemies of liberty and mass murderers.

No comments:

Post a Comment