April 24, 2008 | On May 3, 2007, ten Republican candidates aspiring to succeed George W. Bush as president debated at the Ronald W. Reagan Library, where they mentioned Reagan 21 times and Bush not once. By raising the icon of Reagan, they hoped to dispel the shadow of Bush. Reagan himself had often invoked magic -- "the magic of the marketplace" was among his trademark phrases and he had been the TV host at the grand opening of Disneyland, "the Magic Kingdom," in 1955. Evoking his name was an act of sympathetic magic in the vain hope that its mere mention would transfer his success to his pretenders and transport them back to the heyday of Republican rule.

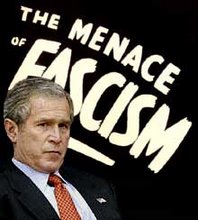

Bush's second term has witnessed the great unraveling of the Republican coalition. After nearly two generations of political dominance, the Republican coalition has rapidly disintegrated under the stress of Bush's failures and the Republicans' scandals and disgrace. The Democrats have the greatest possible opening in more than a generation -- potentially. They should pay strict attention to how Bush has swiftly undone Republican strengths as an object lesson.

On September 10, 2001, Bush was at the lowest point in public approval of any president that early in his term. It was a sign that he seemed destined to join the list of previous presidents who had gained the office without popular majorities and served only one term. After the terrorist attacks of September 11, Bush's fortunes were reversed, and he was no longer seen as drifting but masterful. Now he appeared to take his place in the long line of Republican presidents who had preceded him. He acted as though his astronomical popularity in the aftermath of September 11 ratified whatever radical course he might take in international affairs and vindicated whatever radical policies and politics he might follow at home.

Vice President Dick Cheney assumed control of concentrating unfettered executive power, a project to which he had been devoted since he had served as the assistant to presidential counselor Donald Rumsfeld in the Nixon White House. Karl Rove, the president's chief political strategist, took charge of subordinating federal departments and agencies to the larger political goal of achieving a permanent Republican realignment through a one party state -- another Nixonian objective, run by another Nixonian. Cheney and Rove's complementary efforts gave the substance to the radical theory of the "unitary executive."

In 2004, Bush swaggered through his reelection campaign, still swept along on the momentum from September 11. He and Rove did not consider the perverse and unprecedented illogic of Bush v. Gore as anything but a rightful decision. They did not see the means by which he became president as artificial, making his position inherently weak and unstable. Bush took occupying the office itself and September 11 as tantamount to a resounding mandate for his radicalism. Nor did Bush or Rove view Bush's steady and precipitous decline in popularity as cause to reconsider their preconceptions. After the Afghanistan invasion, Bush's numbers tumbled until he ramped up the campaign for the invasion of Iraq, after which his standing dived again, only to spike once more after the capture of Saddam Hussein, only to fall again. Nonetheless, Rove drew no lessons from these warnings, except that war and terror served as indispensable political weapons to sustain Bush. On this rock, Rove proposed to build a reigning party.

After the 2004 election victory, Rove's former political deputy and Republican National Committee chairman Ken Mehlman said, "If there's one empire I want built, it's the George Bush empire."

Perhaps the most considered, comprehensive and boldest analysis after the 2004 election came from two English journalists, writers for The Economist magazine, John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge. In their book, The Right Nation, they conflated Bush's unilateralism, the religious right, and the conservative counter-establishment of think tanks and foundations with American exceptionalism. "Today, thanks in large part to the strength of the Right Nation, American exceptionalism is reasserting itself with a vengeance."

They categorically declared that the realignment Rove was seeking had at last appeared. Bush's reelection was the crowning moment of the entire Republican era, setting it on a firm foundation for a generation to come. "Who would have imagined that the 2004 presidential election would represent something of a last chance for the Democrats?" they wrote. "But conservatism's progress goes much deeper than the gains that the Republican Party has made over the past half century or the steady decline in Democratic registration. The Right clearly has ideology momentum on its side in much the same way that the Left had momentum in the 1960s."

The Economist's correspondents were Tories in search of a promised land after the Labour Party became the natural party of government in Britain with the post-Thatcher crackup of the Conservatives. The United States was a fantastic canvas for their thwarted dreams. They were delirious to discover that while conservatism had fallen from grace and favor in Britain it held every lever of national power in the New World. "Thatcher could never rely on a vibrant conservative movement to support her (unless you regard a couple of think tanks as a movement) while American conservatism has been going from strength to strength for decades," they wrote with undisguised envy.

At least in one way the Republican triumph in 2004 echoed British political history, resembling that of the British Liberal Party in 1910. "From that victory they never recovered," wrote George Dangerfield in The Strange Death of Liberal England. But the strange death of Republican America, the supposed "Right Nation," cannot be attributed to the same reasons as the decline of Liberal England, a complacent faith of good intentions bypassed and trampled by events that it presumed to understand as it drifted into the dark passage of world war.

The guiding assumption of American politics was that Bush's presidency was girded by a stable conservative consensus and that politics would operate on this consensus into the foreseeable future. In this view, Bush became not only the most recent expression of Republican supremacy but also its strongest. It was a curious refraction of the consensus school of the 1950s that envisioned American politics as an unbroken thread of liberalism.

Next page: The scale of the Bush disaster is larger than any cataclysm since then

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. I.U. has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is I.U endorsed or sponsored by the originator.)

The Nazis, Fascists and Communists were political parties before they became enemies of liberty and mass murderers.

No comments:

Post a Comment