Friday, May 4, 2007

Is Rudy Certifiable? Seems, He Just Might Be.

...and, even more importantly, can we keep people who should be in the Nuthouse out of the White House, this time?

Many New York political pros believe Rudy Giuliani—former mayor, hero of 9/11, and now presidential candidate—is, quite literally, nuts.

The author asks whether Giuliani's lunatic behavior could be the ultimate campaign asset.

by Michael Wolff June 2007

There's no politician more fun to write about than Rudy Giuliani. He's your political show of shows—driven to ever greater public outlandishness by a do-anything compulsion always to be at the center of attention. At some point, when he was New York's mayor, it seemed to stop mattering to him that this attention was, for his political career, the bad kind of attention.

Politics appeared no longer to be his interest; to prove, over and over again, that it's his right—his art, even—to be at the center of attention was. Even this does not really explain the implausibility, and entertainment, of Rudy as a politician.

Rudy Giuliani and his third wife, the former Judith Nathan, who has become a colorful distraction for his campaign.

The explanation for what makes Rudy so compelling among people who know him best—including New York reporters who've covered him for a generation, and political pros who've worked for him—is simpler: he is nuts, actually mad.

Now, this line should be delivered with the proper timing (smack your head in astonishment when you deliver it). And it implies some admiration and affection: he's an original. But it is, too, a considered political diagnosis: every student of Rudy Giuliani—indeed, every New Yorker—has witnessed, and in many cases suffered, his periods of mania, political behavior that, in the end, can't have much of a rational explanation.

So, if you are not from New York, if you haven't had the pleasure of what Jack Newfield, that querulous old-school New York City columnist and reporter, called "the Full Rudy"—also the title of his 2002 book about the former mayor—you perhaps cannot appreciate our sense of emperor's-new-clothes incredulity. Despite what's in front of everybody's face—behavior that's not only in the public record but recapped on the front pages every day—becoming president could really happen for Rudy.

No, that is wrong: virtually every Full Rudy veteran expects the implosion to happen any second. It's in some bizarro parallel reality that the Rudy campaign achieves verisimilitude and even—strange, too, when you consider the cronies and hacks who surround him—appears, at times, adept.

It's a Catch-22 kind of nuttiness. What with all his personal issues—the children; the women; the former wives; Kerik and the Mob; his history of interminable, bitter, asinine hissy fits; the look in his eye; and, now, Judi!, his current, prospective, not-ready-for-prime-time First Lady—he'd have to be nuts to think he could successfully run for president. But nutty people don't run for president—certainly they don't get far if they do.

Newfield, who died in 2004, desperately, and to little avail, tried in his short, apoplectic book to demonstrate the existence of a real Rudy as opposed to the post-9/11 heroic Rudy. "Are you crazy? He's just insane," Newfield kept yelling at me over lunch one day, when I was trying to come up with a strategic explanation for Rudy's wild swings of temperament, judgment, and sense of proportion. (Similarly, Newfield quotes the New York politician Basil Paterson as saying Giuliani has "a devil in him," and Giuliani's former school chancellor Rudy Crew as diagnosing a "very, very powerful pathology," and former New York congressman Rev. Floyd Flake as seeing in Rudy, simply, a deep "mean streak.")

I argued, having voted for Rudy once, that, in certain contexts, nuttiness—for instance, his need for virtually round-the-clock media attention and affirmation—can be a positive governing approach, as well as an effective public-relations strategy. Rudy's manic domination of the city's airwaves and consciousness during New York's most disturbing crime years, when many people felt the city was beyond anybody's control, was palliative (David Dinkins, his more modest predecessor, always seemed overwhelmed). And, of course, his hysteric nature was part of what enabled him to appear so reassuring on 9/11: When everyone is crazy, he, being actually crazy, is calm. When everyone is stunned, he's expressive. (He may be the best off-the-cuff speaker in politics—conversational, witty, personal.)

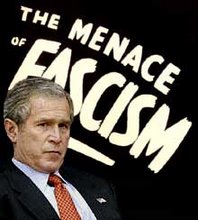

Here Newfield went on, during lunch, to harangue me about the willful blindness, the consensus cowardice of the media. We (that is, we in the media) quite refuse to acknowledge the possibility that an entirely inappropriate character (a "nutso" was, I believe, Newfield's term) might be able to navigate all the hurdles and scrutiny of a campaign and actually become president. (The instances—e.g., Howard Dean, Wesley Clark—when oddball candidates do get dinged reinforces the belief that, if you make it, you deserve to make it.) The better your poll numbers are, and the closer you get to being president, the more that certifies you as being sane enough to be president (the Bush and Cheney example notwithstanding).

New York magazine, for instance, has been covering Rudy's antics for a generation. The magazine was, itself, subject to a famous blitz of Rudy loopiness: he banned from city buses an ad for the magazine with a tagline saying it was "possibly the only good thing in New York Rudy hasn't taken credit for."

But its recent cover story on the Rudy presidential phenomenon was written by a neophyte political journalist rather than one of the legions of New York reporters who've been gobsmacked over the years by Rudy (there's a whole new generation of reporters who don't know the real Rudy).

So instead of being a story about the sheer preposterousness, the zaniness and lunacy, of the notion of Rudy as president—the exceptionalness of the whole enterprise—it was about, in essence, the logic of perception.

Rudy is, necessarily, what others see him as—that was the magazine's eminently politic point.

Similarly, Newsweek, in its Rudy cover story, made the case for transformation by polls—you are what an unexpected number of people are willing to believe you are, no matter how outside the realm of credibility and reason that might be. In both critiques, Rudy is far along in the process of making himself into a realistic presidential being, a legitimate, if curious, front-runner, a man for all seasons, a plausible model—this character famous for his dramatic mood swings—of steadfastness and determination. If he doesn't implode, then, in fact, he's sound.

Page of 4 > >

(In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, this material is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. I.U. has no affiliation whatsoever with the originator of this article nor is I.U endorsed or sponsored by the originator.)

The Nazis, Fascists and Communists were political parties before they became enemies of liberty and mass murderers.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment